“We need to know where we live in order to imagine living elsewhere. We need to imagine living elsewhere before we can live there.” – Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination

Traditionally, historically, conceptually, rhetorically – a theatre is a haunted place. Or, better to say – a theatre is a haunted house. This is superstition ingrained to such a quotidian extent that the ghost is a common part of professional parlance. Late at night, when the house is empty, the ghost light glows onstage, to keep the ghosts safe after everyone else has left.

Sometimes the whole building is called a house, like an opera house; but more often the house is where the audience sits, and the stage is something else altogether. The stage and the house together make up the whole of a theatre. Which one is haunting and which is haunted? If the audience sits in a dark house, we can be read as the ghosts, longingly looking through that fourth wall toward the warmth of movement onstage. Or, if the audience is a house, and a house needs a ghost, then what is enacted onstage is also the haunting, performed for our pleasure.

The ghost light is what beckons after hours so that the ghosts know how to find their (our) way back home. What kind of a homecoming is haunting? Queer and trans people are often, necessarily, adept at finding and making homes beyond the ones we’ve left. Home – whether we think of that as family, or house, or town – is not always a place we’re welcome to imagine staying, or living. Sometimes, often, queer and trans people aren’t given the opportunity to leave, to live. Invoking the language of the ghostly carries an implication of violence and loss, but also a refusal to stay dead and gone, a refusal to do what we’re told. The ghost is not only a metaphor but a kind of queer methodology. Queer and trans people are often, necessarily, adept at loss – a haunted virtuosity. But to be haunted is a gift, one that we practice with and for one another.

A theatre is a haunted house and that’s simply another way to say that a theatre is a structure of feeling; a structure we use to practice haunting. How do we learn to be haunted, except through repetition over time? Avery Gordon tells us that “being haunted draws us affectively, sometimes against our will and always a bit magically, into the structure of feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition.” This is as good a theory of theatre as any, although it wasn’t explicitly intended as such. Gordon is a sociologist and her interest, in her brilliant Ghostly Matters, is in our ability to see and follow the ghost, an urgent, insistent figure whose presence may alert us to some untold story or unfinished business. One way to follow the ghost is to the theatre. Gordon offers us our own choreography: follow the ghost, so that we may see or feel or know what happens. “The way of the ghost is haunting, and haunting is a very particular way of knowing what has happened or is happening… Of one thing I am sure: it’s not that the ghosts don’t exist.”

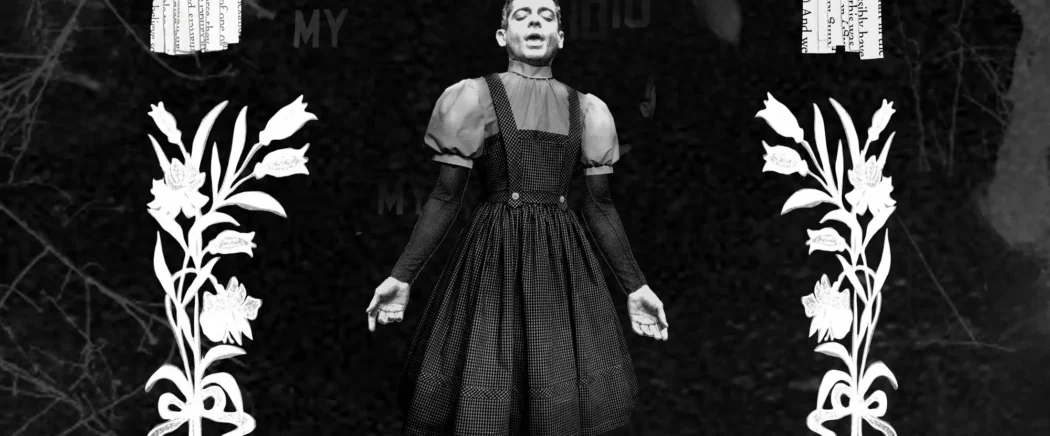

Jack Ferver’s My Town is haunted and haunting, and Jack restlessly travels, their body often following their hands, oscillating between seemingly binary options. Their stage is both before and after, the black and white that brackets Dorothy’s voyages away from and then back home. These uncanny split or doubled town(s), twin houses, are mapped in shifting detail in Jeremy Jacob’s video and scenic design, tracing out the contours of each stitch as it’s made, and then again in duplicate. One house emerges through its opening windows, facing the house of the audience – another twin – and then becomes an eye looking back at us, Jack held in the space between, in the lights. The uncanny is famously both homely and unhomely, familiar and frightening. We see, we are seen. Where else will the ghosts take us?

J de Leon is NYU Skirball’s Director of Engagement and teaches queer studies courses for NYU Gallatin.