Transition begins in language, the rest following in the wake of words. Trans and nonbinary names and pronouns are poetry – following Audre Lorde’s argument, in “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” that “poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” To reconfigure one’s self in language – name and or/pronoun – is to indulge in an idea of another way of being in the world, to imagine a way into or out of something binding, and to hold open space for a different sense of movement for one’s self instead – the possibility of change. Our names and pronouns are spoken into the world to give it a new shape. These are also demands made of another: a new name or unexpected pronoun asking for an affirmative repetition, a performative reflection: mirror re-staging. Gender is never accomplished alone. It relies on an audience that either affirms and repeats – or refuses – one’s desire to be seen and understood in a way that breaks with expectation.

If our names, bodies, voices, pronouns, and pasts all confess us in various ways, then a new school of trans-confessional poetry takes up confession and expands the potentiality in these experiences. Trans poets practice and play with naming in their work, complicating linear narratives of transition and dreams of stealth or passing by articulating their relation to naming as a form of self-making. In her poem “Pardon My Gender,” Joshua Jennifer Espinoza calls this a practice of “gushing bloody dreams of escape,/ of listening to one’s self and caring for other selves.” Nonbinary poet Paige Lewis calls naming “the only power we’re left with;” in their poem “Last Night I Dreamed I Made Myself,” they elaborate this power in relation to their own dream of self-making:

not anything polished –and I think

about how hard it is for me to believe

in the first Adam because if Adam

had the power to name everything,

everything would be named Adam.

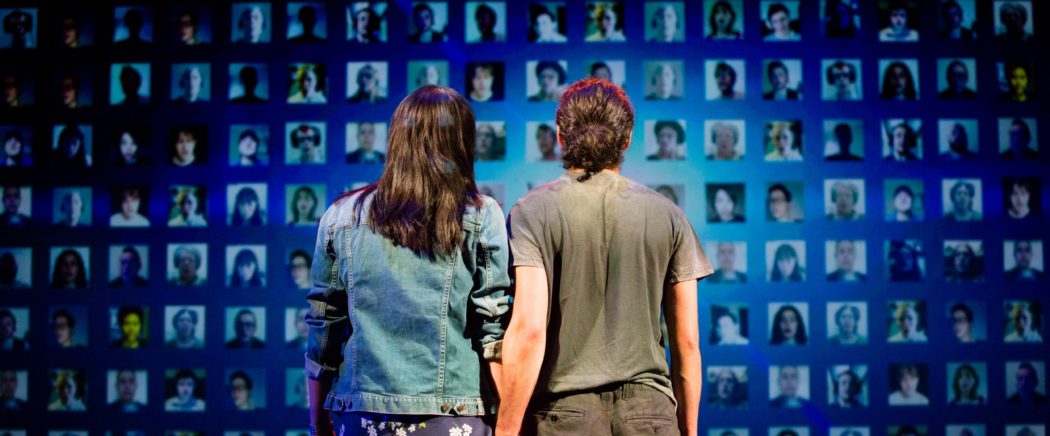

Adam Kashmiry is the eponymous Adam in the National Theatre of Scotland’s staging of his story, but the many Adams he shares the stage with in his autobiographical performance help him to open his story in a way that underlines the fiction of singular autobiography – both with past-Adam and the virtual chorus that beams in from around the world to sing, their voices shaping the space in which his story is told.

Adam is a story of borders and bodies, the ways in which we work to make our selves home, in excess of the logic that structures so much of the world: citizenship, nationality, gender – and the ways these logics often work in tandem to maintain suffocating social and political norms. This is a story told in many voices, underlining the rich, differing complexities of trans and nonbinary experiences, with a virtual chorus that also speaks to the ways virtual worlds can offer opportunity to dream with others. The theatrical setting offers an opportunity to spectacularize the openings Adam found on the internet, all the voices he found to affirm and guide his own experience gathered in a chorus that exults one story, one Adam, among many. These many Adams speak to Lewis’s playful description of the pleasure and power of naming oneself anew, and of finding others to share that experience, to listen to and dream and share “gushing bloody dreams of escape.”

J de Leon is Assistant Director, Engagement at NYU Skirball. They hold a PhD in Performance Studies from NYU.