On March 30, 1982, hundreds of thousands of Argentine workers took to the streets of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, and other major cities to protest against massive layoffs and factory closures, in the biggest expression of popular discontent with the dictatorship that had seized power in 1976. Two days later, on April 2, the head of the military Junta, General Galtieri, addressed a two-hundred-thousand strong, jubilant crowd celebrating the landing of Argentine troops that same morning on the Falkland Islands – or Islas Malvinas – the windswept, British-occupied Southern Atlantic archipelago mostly populated by sheep and seabirds.

Following two and a half months of relentless propaganda about the Argentine army’s heroic victories, audiences in Buenos Aires suddenly woke up to the reality of humiliating defeat on the hands of the Royal Navy. 649 Argentine soldiers had lost their lives – many of them eighteen-year-old conscripts deployed to the islands as cannon fodder, victims of hunger, hypothermia, and tortures inflicted by their own officers as much as of British bombs and gunfire. 255 British soldiers, as well as three islanders, also died during the fighting. The following year, the Argentine dictatorship was ousted and some of the generals prosecuted for human rights abuses. Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister whose popularity had hit rock bottom just before the war, cruised to re-election easily.

Veterans of a war fought, quite literally, at the end of the world, the Argentine youths returning from a traumatic experience of defeat were met with widespread indifference – as were, to a lesser extent, the British troops coming back from what seemed an easy victory in a remote outpost, as soon forgotten as it had been cheered on. Yet, even though a Malvinas Museum has now opened in the space of ESMA, Buenos Aires’ former Naval Academy and also one of the dictatorship’s largest concentration camps – now a memory and human rights site – the ex-combatants’ voices don’t easily fit into historical narratives in the country, torn between the plight of the victims of state terrorism and the, in recent times, more and more open vindication of military violence. To give an account of themselves as soldiers and victims has, for decades, been an almost impossible challenge for the survivors of Malvinas/Falklands.

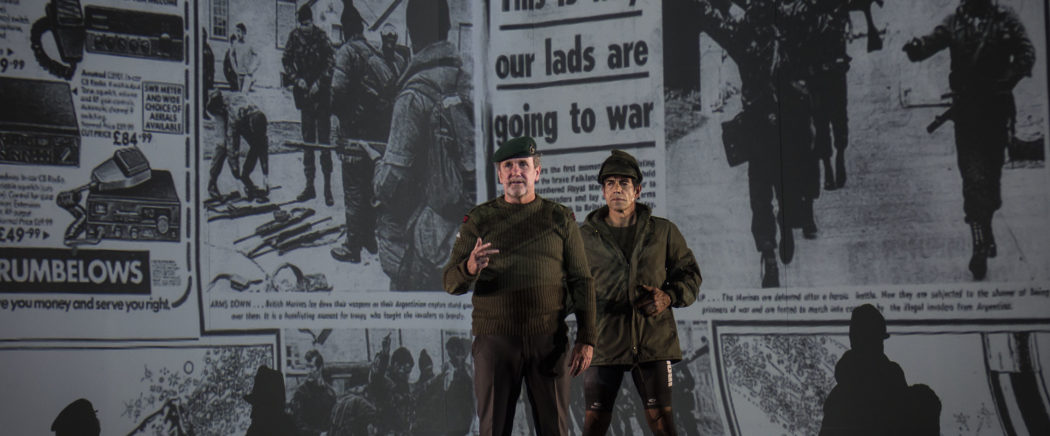

Now, more than thirty years after the event, acclaimed Argentine director and documentary theatre pioneer Lola Arias’s Minefield has ex-combatants from both sides tell their stories to what had perhaps always been their only possible audience: one another. “The Brits don’t speak Spanish, we Argentines don’t speak English,” says one of them. “But somehow we understand each other.”

Jens Andermann is a Professor in NYU’s Department of Spanish & Portuguese. He works on modern Latin American arts, film, literature, architecture and material culture, and their intersections with extractivism and the legacies of coloniality. He is an editor of the “Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies.”