Toshiki Okada’s generation of Japanese 30- to 40-somethings came of age as Japan’s economic bubble burst in the 1990s, with an estimated 50%+ of whom remain either unemployed or underemployed. With dim prospects for catching up with either their parents (who rode the wave of economic stability that preceded them) or the generation that followed (who entered a workforce already adapted to new economic realities), this “Ice Age” group has been the target of national policy initiatives, hand-wringing editorials, and sociological studies. As a voice of this generation, Okada has become one of Japan’s most influential contemporary theater artists, and a mainstay of international performance festivals. “The generation I belong [to] believed somehow that Japan’s development would continue forever,” Okada said in 2011. “We were so confused because the situation was changed almost suddenly … I don’t think they have any hopes.”¹ The first chelfitsch piece to attract international attention, Five Days in March (2004)² portrays the mixture of panic, helplessness, and passive alienation felt by many young Japanese at the onset of the Iraq War — a conflict both far away, and yet creating reverberations in the intimate here and now of the characters.

Since the 3/11/11 tsunami off the coast of Fukushima, Okada’s focus has widened to encompass the scope of that catastrophe — one that, as Jean-luc Nancy has written, entails “chains of correlation that extend out from that starting point.”³ Okada’s recent works meditate not only on Japan’s “lost generation” but on the confusion, malaise, and paralysis that seems to have pervaded a global generation, uncertain about the future — both theirs and the planet’s.

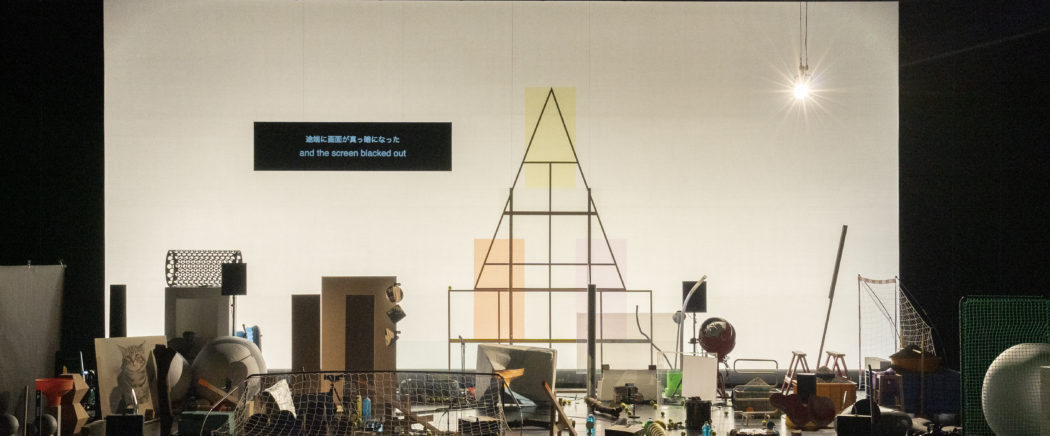

In collaborative and commissioned works such as Zero Cost House (2012) and Time’s Journey Through a Room (2016) Okada explores transhistorical, transnational anomie brought on by contemporary globalization.³ Yet Okada’s work is never wholly despairing or nihilistic. He has cited Samuel Beckett and Bertolt Brecht as early influences, and in the spareness and patience of his work is the space and time to imagine the possibility of, and desire for, human connection and (perhaps) a hopeful turn toward a post-human future.

1. “Toshiki Okada/ chelfitch @ Holland Festival 2011,” https://youtu.be/I–xDwTfho4 (accessed 11/22/2019).

2. “Five Days in March” had its U.S. debut in 2009. For this production and all subsequent English-language subtitles and performances, New York-based playwright Aya Ogawa provided indispensable expertise in translating Okada’s signature “hyper-real” contemporary idiomatic Japanese.

3. After Fukushima: The Equivalence of Catastrophes, trans. Charlotte Mandell (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015), 30.

4. For a deeper examination of Okada’s work in relation to time (via the work of Jacques Rancière and Michel Foucault, see Sara Jansen’s fine essay, “‘In What Time Do We Live?’: Time and Distance in the Work of Toshiki Okada,” https://thetheatretimes.com/time-live-time-distance-work-toshiki-okada/ (accessed 11/23/2019).

Karen Shimakawa is an Associate Professor of Performance Studies and Co-Associate Dean of Faculty in the Tisch School of the Arts, and affiliated faculty at the NYU School of Law.