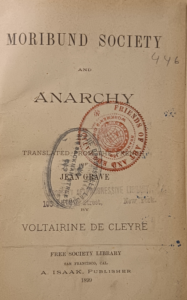

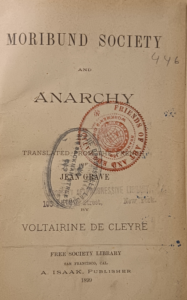

These markings give us a glimpse into the intimacy of everyday anarchism. They reveal not just relationships to the texts themselves, but the markings quietly offer us a moment to consider a networked community of anarchist thinkers and doers–where they reside and gather; how they mourn; the expected and–perhaps–unexpected associations they form. A copy of Voltairine de Cleyre’s Moribund Society and Anarchy shows us the circulation of anarchist thought. The copy, from 1899, is stamped with the various collective libraries the title passed through: the Brownsville Labor Lyceum (219 Sackman); the Workmen’s Circle Friends of Art and Education Library (also once located in Brownsville); the Progressive Library (106 Forsyth); and the N.Y. Radical Reading Room (180 Forysth).

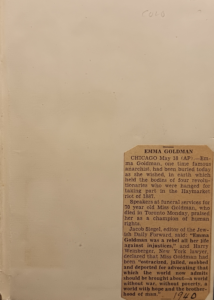

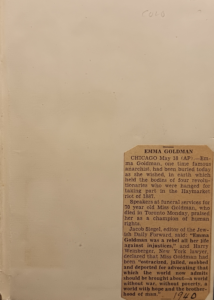

In 1940, an anonymous individual demonstrated a moment of anarchist memorialization and affinity by carefully cutting out a newspaper clipping of Emma Goldman’s obituary and gently pasting it into the lower left-hand corner of the frontpage of Goldman’s 1911 Anarchism and Other Essays.

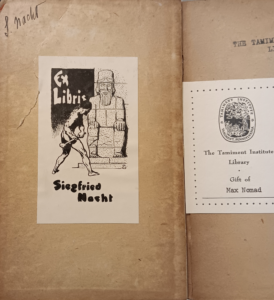

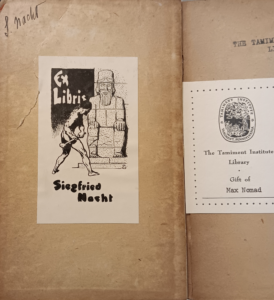

Renowned anarchists make their mark, too, in everyday ways. Siegfried Nacht (also known as Stephen Naft and Arnold Roller), both signs his copy of Philosophie de L’Anarchie and affixes his personalized ex libris: a black and white image of a naked person swinging a sledgehammer at a stone idol. On the opposite page, there is a dedication which notes that the book has been donated to the Tamiment Institute Library (then at Camp Tamiment) by Nacht’s brother, Max Nomad. Nomad, who outlived Nacht by nearly twenty years, honors the life of his brother inside a text that Nacht clearly loved as Nacht devoted his name to its pages more than once.

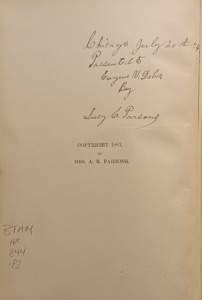

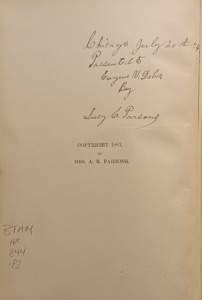

Readers may be familiar with the adoring words that Lucy Parsons and Alfred Parsons left to one another, respectively, in Anarchism and Life of Alfred Parsons. Readers may be less aware that Lucy gifted a copy of Anarchism to Socialist Eugene Debs on July 20, 1894–an occasion she commemorated on the inner pages of Tamiment’s copy of the text.

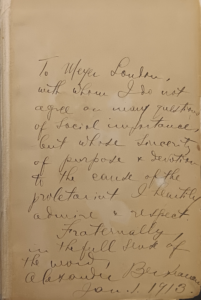

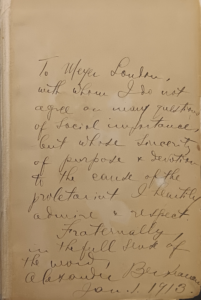

In 1913, on New Year’s Day, just months before he organized demonstrations of striking United Mine Workers, Alexander Berkman wrote a note to another Socialist, Meyer London, inside a copy of Berkman’s Prison Memoirs: “To Meyer London, with whom I do not agree on many questions of social importance, but whose sincerity to the cause of the proletariat I heartily admire and respect. Fraternally, in the full sense of the word, Alexander Berkman, Jan 1. 1913.”

These stamps, clippings, handwritten notes, inscriptions, and ex libris could be thought of, on the one hand, as wholly mundane. Another way to think of them is that, below the surface, they are rippling reminders that someone once committed themselves every day to engaging practices, thinking, and actions that are participatory, decentralized, voluntary, non-hierarchical, relational, and liberatory. And that you can too.

NYU Special Collections, is open to the public by appointment: Mondays-Fridays, 10-5pm.

Shannon O’Neill is Curator for Tamiment-Wagner Collections at NYU’s Division of Libraries.