This essay is a commission published partnership with the Downtown Collection at NYU’s Fales Library for “COVID19 & Its Afterlives”. Learn more about the series here.

It is two archival records, two AIDS records held at the Fales Library and Special Collections—a sketchbook and a zine—each rendered by artist-activist Frank Moore that in words and images get at the core of activist archiving amidst a still unfolding pandemic.[1] “Activist archiving” describes the archival care activists perform as part of their efforts to engender social change.[2] In these records Moore charts what it means to do this archival work in the context of the AIDS epidemic. He documents the collaborative processes undertaken to create and sustain community-based arts organization Visual AIDS’s Archive Project. This is an AIDS archives by and for the community of artists living with HIV/AIDS. Since 1994 they have documented AIDS arts-activism and developed the infrastructure to maintain it. The Archive Project and its digital counterpart, the Artist+ Registry, safeguard vital records for remembering AIDS arts-activism. These records also impart to us now the responsibility to activate them. Records can revitalize the epidemic’s past in ways that contest and transform twenty-first century pandemics, from AIDS to COVID-19, that are undergirded by racism, sexism, ableism, poverty, homo- and trans-phobias, and colonialism.

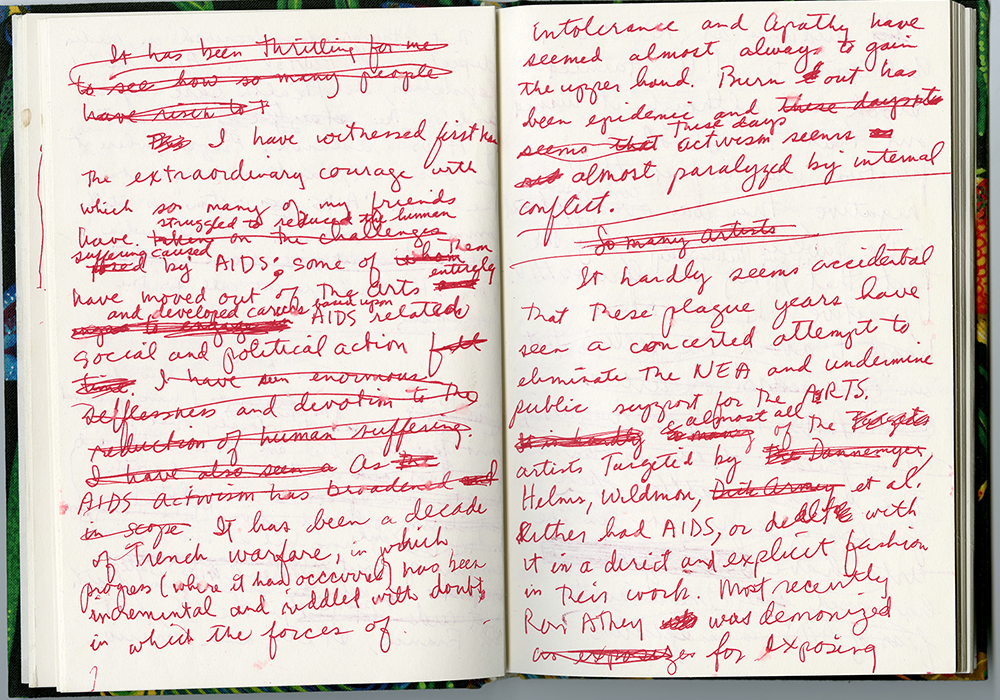

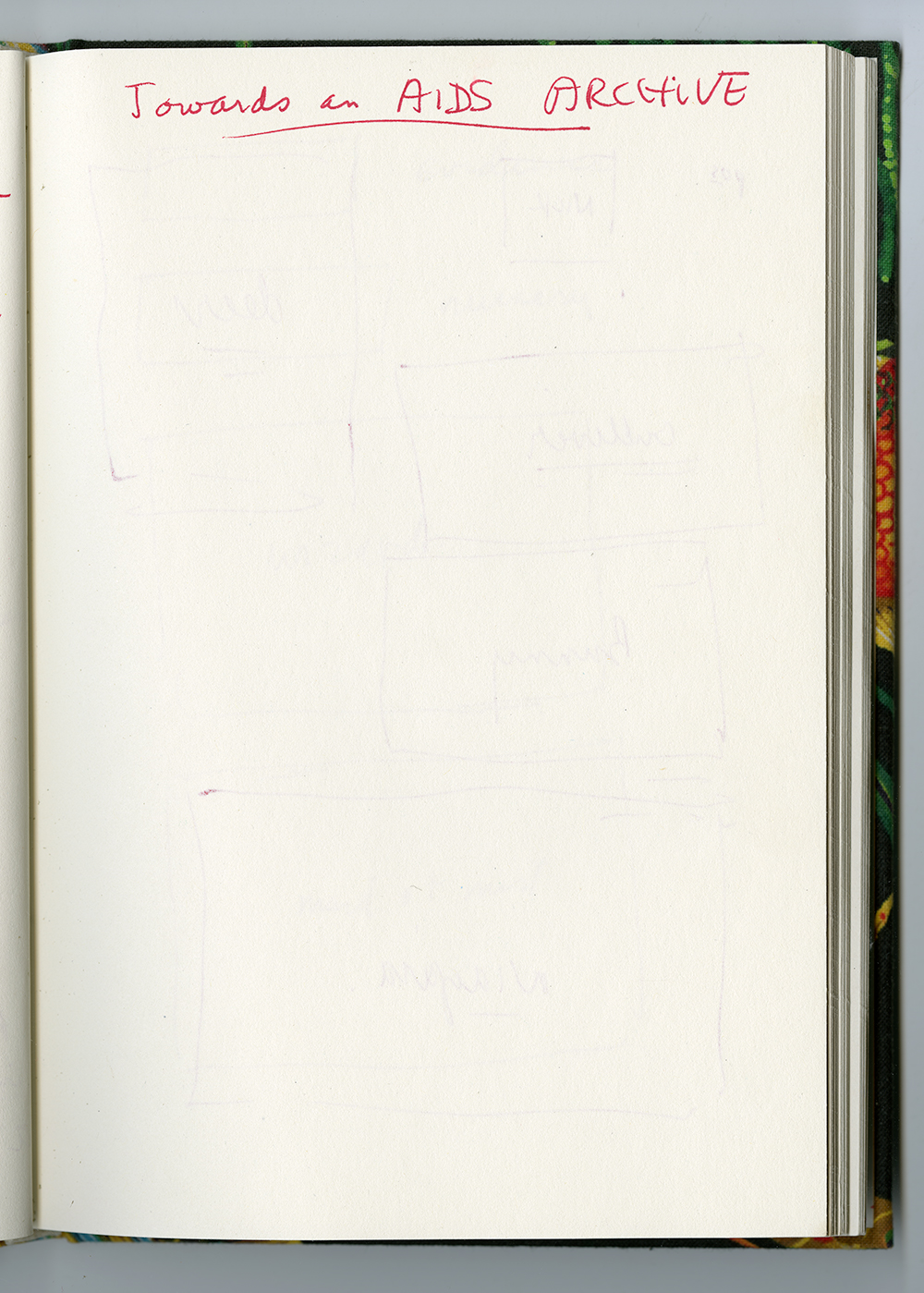

It is a few pages of Moore’s sketchbook #82, one he used between 1993 and 1995, to which I return again and again. The sketchbook, one of many spanning from the 1970s to Moore’s 2002 death is part of his 44.75 linear feet of personal papers documenting his career as a painter and activist. His sketchbooks offer up notes, tirades, little sketches, and bigger plans. My deep dive into Moore’s papers in the summer of 2016 was an attempt to uncover what AIDS activist-scholars Debra Levine and David Román respectively term the “impulse to archive.”[3] This is an impulse I am certain Moore felt too. I found less than I’d hoped to about Moore’s involvement as a co-founder of the Archive Project for many days. It was not until I read this sketchbook entry that I began to be able to hear the echoes of Moore’s voice. Moore’s absence in my research on a constellation of archives that keep the history and work of AIDS activisms alive is loud. This entry is one of vanishingly few means to gain insight into Moore’s activist archiving.

![handwritten page in red ink: The intolerance and hatred by the AIDS crisis has proved a potent political weapon. [line] There will always be political leaders who will seek to harness intolerance and hatred to further their own political agenda. To the extent that this power depends upon distortion and misinformation, it will become increasingly vital to collect and preserve a wealth of information and documentation of the AIDS crisis to prevent the manipulation of history driving intolerant agendas.](https://nyuskirball.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FM4252small-732x1024.jpg)

I suspect that the sketchbook entry envisioning the archives predates Moore’s involvement in the daily labors of activist archiving. It was Moore who issued an invitation in early months of 1994 to friend and art critic David Hirsh. Hirsh told me in an interview that it was at the close of a studio visit that Moore inquired: “Would you like to start an archive of slides by artists who have died of or have HIV/AIDS?”[6] Moore’s entry frames the urgency of the archival imperative.

By 1994, when Moore and Hirsh recruited a dedicated committee of fellow creative workers to develop the Archive Project, the AIDS crisis in the United States had hit its “deepest darkest point.”[7] That year the New York City Department of Public Health estimated that a full thirteen percent of the city’s artists, 8,500 individuals, were living with HIV or AIDS.[8] Activists by then had spent over a decade engaged in what Moore described as “trench warfare.”[9] A decade of extreme effort in which, he continued, “progress (where it has occurred) has been incremental and riddled with doubt, in which the forces of intolerance and apathy almost always seem to gain the upper hand.” Moore emphasized, moreover, that “burn out” had reached “endemic” status and was provoking internal conflicts stalling activist response.[10] As an HIV-positive artist, even one who was “sort of lucky” when it came to his health, resources, and career successes, Moore was intimately familiar both with the atmospheric “background anxiety,” and with the daily tasks requisite to maintaining life—seeing multiple doctors, taking daily pills (33), just keeping up.[11] These factors led many positive artists to slow or stop making work altogether—an artistic demise, a death that often preceded that of the physical body and precipitated the loss of work, of artistic legacy.

Moore was a catalyst in Visual AIDS’s turn to archiving as the “heart” and “backbone” of the organization’s work.[12] The Archive Project, renamed posthumously in Moore’s honor, became and remains a collection of 35mm slides and digital files of artworks, along with press clippings, artist statements, printed invitations, and small artworks. The two parameters for placing records in the archives’ care were established from the project’s start and remain the same to this day: they collect the records of people who self-identify, first, as artists, and second, as living or having lived and died with HIV or AIDS. The latter implicitly requires an ability and willingness to disclose one’s serostatus in a publicly accessible archives. It is now the largest registry of work by artists living with HIV/AIDS.

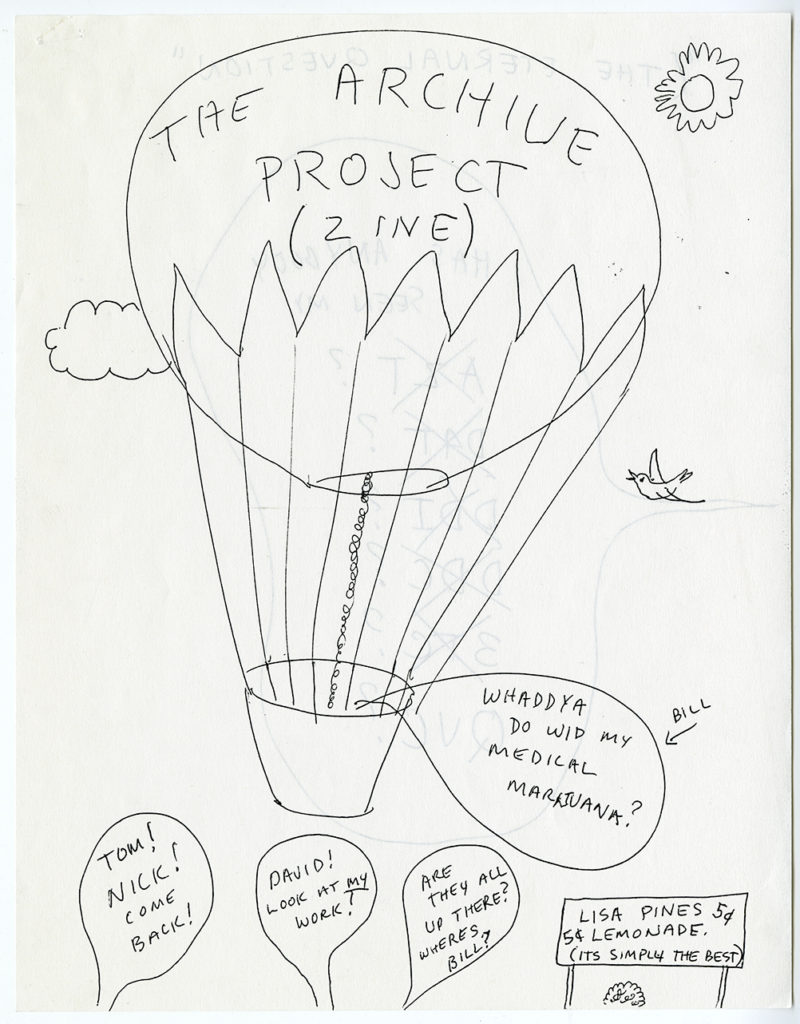

I trace the development of the Archive Project through Moore’s renderings. The Archive Project (Zine) created by Moore around 1995 articulates, with dry, dark wit, the day-to-day realities and affective experiences of activist archiving in an epidemic emergency. The 8-page zine, xeroxed and stapled, is both unsigned and undated.

I first encountered it in Visual AIDS’s organizational files in their Chelsea office, where the Archive Project occupies a central space. The small, bustling, art-filled room doubles as a community center; artist members, collaborators, and visitors came in and out during the weeks I spent researching there. Visual AIDS’s inactive organizational records, including the Zine, have subsequently found a home at the Fales. I had been eager to interview Hirsh, the Archive Project’s surviving co-founder, during fieldwork in 2015 and 2016. However, neither Visual AIDS staff nor I could find anything about his whereabouts after the mid-1990s. It was not until 2018 when artist Eric Rhein, one of the early members of the Project, dialed a number found in an old file and discovered that it still belonged to his friend and collaborator Hirsh, that he was reunited with Visual AIDS. In a series of interviews Hirsh offered insights to me that are now his sole possession, including about Moore’s efforts and motivations. He confirmed for me that Zine was Moore’s delightful creation.

![Page from a zine drawn in black ink on white paper; the drawings reverse side of the page partially visible. “MINDFUL/LANDFILL” “’THE EARTH WORK PERIOD.’” Line drawing of a full trash can with a lid and the words “(LIFE’S WORK)”. A rat looks up at the trash can and a spider crawls up the side. Text next to the trash can reads: “HIS NAME WAS ROBERT. THE CUTEST BOY IN THE EAST VILLAGE — SOMEONE SAID. MOLTO TALENTO (GREAT ANIMAL SCULPTURE) NOW LANDFILL. A line cuts through the middle of the page. Text reads “THE DAILY MULTIPLE CHOICE. EATING < YOU / FOI GRAS / MACRO* / ASS [CROSSED OUT] / IT / OUT. REACHING < OUT / NIRVANA / THE END [CROSSED OUT] / YOU*. LOVING< UNSAFE [CROSSED OUT] / YOU* / KINDNESS / EVERY MINUTE. TAKING < MY TIME* / ANYTHING / OVER / PILLS / ON TOO [CROSSED OUT] MUCH Line drawing of a hand holding a rotary telephone. Speech bubble coming from the phone reads “Press one to say yes. Press two to say no. Press three to say maybe. Press four for xtra onions. Press five if you have a rotary.” Speech bubble from the top of the page reads: “Its for you — its you're A. Mother [drawing of heart] B. Doctor $ C. Pharmacy $ D. Coroner ! E. Collection Agency (Do they collect (contemporary?) Art?). Speech bubble from the right side of the page “Tell them im A. Dead B. Painting C. Retching D. Asleep E. In Love F Broke(n) [crossed out:] (reading Proust) (jerking off!)](https://nyuskirball.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/APZineMindfulLandfillsmaller-800x1024.jpg)

![Line drawing of a hand holding a rotary telephone. Speech bubble coming from the phone reads “Press one to say yes. Press two to say no. Press three to say maybe. Press four for xtra onions. Press five if you have a rotary.” Speech bubble from the top of the page reads: “Its for you — its you're A. Mother [drawing of heart] B. Doctor $ C. Pharmacy $ D. Coroner ! E. Collection Agency (Do they collect (contemporary?) Art?). Speech bubble from the right side of the page “Tell them im A. Dead B. Painting C. Retching D. Asleep E. In Love F Broke(n) [crossed out:] (reading Proust) (jerking off!)](https://nyuskirball.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/APZineTelephonesmaller.jpg)

![“THE ARCHIVE”. Line drawing of rows of books. Some blank, many reading “Dead” “He’s Dead” “Dying” “Sucks”. Speech bubble in the center of the page reading “PARTY?” in big block letters; [crossed out] “isn’t it time when do we get to.” Speech bubble crossed out on bottom of the page in big block letters “DANCE!”. (SORRY!)](https://nyuskirball.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/APZineArchivesmaller-800x1024.jpg)

If always limited in scope and scale, the Archive Project nonetheless ensured that there would be an AIDS record at all. Its remedy eased some of the pervasive hopelessness and fear about the demise of one’s artwork and legacy, saving lives and legacies. “We knew that there were stories that needed to be preserved and retold–not about ‘victims’ but about the universes these artists inhabited,” Moore wrote two years into building the Archive Project.[20] These records “must be preserved” for their “intrinsic value” and “historic (AIDS) value.”[21] For artists with HIV and AIDS, the Archive Project Moore created promised long-term survival as a community with a collective history, even before pharmaceutically facilitated long-term survival for HIV-positive people became possible. Preserving records and passing down AIDS memory is vital; it is the only way Moore believed to ensure that such genocidal violence “never again” happens.[22] He feared that if denied their history, this AIDS history, future generations would say, “Never what again?” He urged us in words that still resonate powerfully at the conjunctions of the AIDS and COVID-19 crises, that we “must fight the weariness that sets in when one thinks of preserving a memory of that which one would rather forget.” Moore offers us a powerful provocation that still needs to be heeded as we live now simultaneously amidst multiple pandemics: “Towards an AIDS ARCHIVE.”[23]

____________

[1] This essay draws from a chapter, “An Archival Cure: Remedy, Care, and Curation with the Visual AIDS Archive Project,” in the author’s forthcoming book, Viral Cultures: Activist Archiving in the Age of AIDS (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022).

[2] Andrew Flinn and Ben Alexander, ““Humanizing an inevitability political craft”: Introduction to the special issue on archiving activism and activist archiving,” Archival Science 15 (2015): 329-335.

[3] Debra Levine, in discussion with the author, Skype, October 28, 2016; David Román, “Remembering AIDs: A reconsideration of the film Longtime Companion,” GLQ 12, no. 2 (2006): 281-301.

[4] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995,” Frank Moore Papers, MSS 135, Box 5, Folder 138, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University.

[5] Jallicia A. Jolly, “What HIV/AIDS Teaches Us About COVID-19,” Medium, June 19, 2020, https://medium.com/national-center-for-institutional-diversity/what-hiv-aids-teaches-us-about-covid-19-7d80766f748b.

[6] David Hirsh, in discussion with the author, New York, NY, November 8, 2018.

[7] Visual AIDS Staff, “The Multitudes of Frank Moore,” “Gallery,” Visual AIDS, November 2012, https://www.visualaids.org/gallery/detail/104.

[8] W. E. Scott Hoot, “Estate Planning for Artists: Will Your Art Survive?” Columbia-VLA Journal of Law and the Arts, 21, no. 1 (Fall 1996), 15.

[9] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995.”

[10] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995.”

[11] Frank Moore, “Frank Moore,” in W. E. Scott Hoot, “Estate Planning for Artists: Will Your Art Survive?” Columbia-VLA Journal of Law and the Arts 1, no. 1 (Fall 1996a): 19.

[12] Esther McGowan, in discussion with the author, New York, NY, May 27, 2016.

[13] Hirsh, discussion, November 8, 2018.

[14] Hirsh, discussion, November 8, 2018.

[15] Rhein, discussion.

[16] Michelle Caswell, “Toward a Survivor-Centered Approach to Records Documenting Human Rights Abuse: Lessons from Community Archives,” Archival Science 14, nos. 3–4 (2014a): 313, https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10502-014-9220-6.

[17] Hirsh, discussion, November 8, 2018.

[18] Lisa Pines, “Forward,” in Arts’ Communities, AIDS’ Communities: Realizing the Archive Project (New York: Visual AIDS, 1996), 6.

[19] Hirsh, discussion, April 25, 2019.

[20] Frank Moore, “The Archive Project: A Larger Vision,” in Arts’ Communities, AIDS’ Communities: Realizing the Archive Project (New York: Visual AIDS, 1996), 23.

[21] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995.”

[22] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995.”

[23] “FM Notebook #82, 1993–1995.”