Johann Sebastian Bach’s Six Suites for Solo Cello (composed around 1720) spent much of the 18th and 19th centuries overlooked as only a series of etudes or technical exercises. In the late 1930s, Pablo Casals made a landmark recording of the suites that brought them out of obscurity and over the past ninety years they have become more and more central to the cello repertoire.¹ While there are multiple musical reasons the pieces have proven such generative material for cellists, it is in many ways their solo-ness itself that makes them so distinctive — a single player making a world by themselves, an instrument that often plays an accompanying role-playing solo, unaccompanied. When I first started studying the suites with my cello teacher, we would comb through the score together to discover how Bach made our primarily monophonic instruments become polyphonic. Bach writes virtuosically schizophrenic solo lines that contain multiple voices. The cello becomes a piano, an orchestra, and a choir not only through the simultaneous sounding of multiple notes but also through fragmented melodies that imply harmony through the juxtaposition of individual notes. Formally, the suites seem to pose the questions: how does the singular become multiple? How does the one become many? How does the unaccompanied accompany itself?

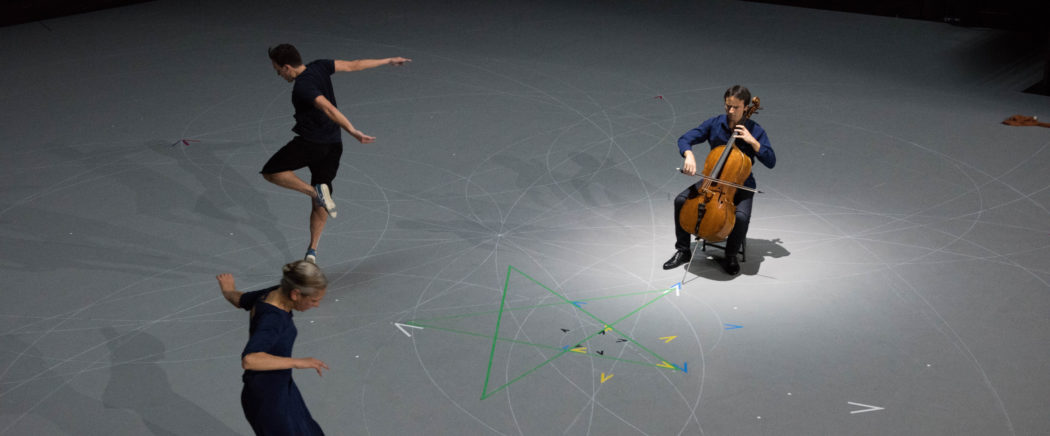

Anna Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Mitten Wir Im Leben Sind/Bach Cellosuiten, choreographed in collaboration with the cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras and members of De Keersmaeker’s company (Boštjan Antončič, Marie Goudot, Julien Monty, and Michaël Pomero), takes Bach’s suites for unaccompanied cello and renders them no longer unaccompanied. The solo suites—already a singular multiplicity, already a one becoming many—become an ensemble work. Motivic patterns become stepping patterns, harmonic motion becomes movement through space, musical structures are rendered visible through their gestures and movement. The cellist and dancers share the stage, the cellist moving positions with each suite and the floor covered with markings: overlapping circles, pentagrams, and spirals, as if to notate what is shared between the musical and choreographic structures unfurling in space together. While inherited relations between music and dance tend to set up a hierarchy between the mediums in which dance takes the stage while music is heard acoustically from off stage, De Keersmaeker’s work puts the music and the dance on the same plane as if to beg the questions: Is the cellist dancing? Are the dancers playing? Who is following whom? Who is accompanying whom?

“Accompaniment,” the noun, means a part that supports, it implies a foreground-background hierarchy, a supportive structure that recedes behind a supported central focus. On the other hand, “accompany,” the verb, signifies a going with, a being present together, an associative companionship. De Keersmaeker’s setting of Bach’s cello suites seems to approach the unaccompanied so as to make a movement from accompaniment to accompanying. The dancers accompany Queyras’ playing in a way that disrupts hierarchies of support. Music and dance are taking up space and time together, they are both parts mutually supporting one another. De Keersmaeker’s title for the work, Mitten Wir Im Leben Sind is taken from a 1524 hymn with text by Martin Luther that translates loosely into “in the midst of life we are in death.” Mitten: in the middle, in the midst, between dance and music, body and instrument, life and death, the one and the many, mutually accompanying.

1. For example, this year Yo-Yo Ma, the world’s most prominent cellist, is in the midst of a two-year project touring marathon performances of all Six Suites in thirty-six locations on six continents in tandem with 36 days of social action in conjunction with the release of a new recording of the suites called Six Evolutions: Bach Cello Suites. This is his third major recording of the suites. In 1983 he released The Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites Complete, his first recording of the suites, and won a Grammy. In 1998, he worked with Sony Classical to create The Cello Suites: Inspired by Bach, a recording of the suites accompanied by a series of six films in which Ma collaborated with an artist in a different discipline to create an interdisciplinary manifestation of each suite (landscape architect Julie Moir Messervy, architect Biovanni Battista Piranesi, choreographer Mark Morris, filmmaker Atom Egoyan, Kabuki actor Bandō Tamasaburō, and ice dancers Jane Torvill, Christopher Dean, and Tom McCamus).

Ethan Philbrick is a cellist, composer, and writer based in Brooklyn. He holds a PhD in Performance Studies from New York University and is currently Assistant Visiting Professor of Performance Studies at Muhlenberg College.