Have you ever been tempted to think about theater as a place where collectivity happens? I think most of us have. It’s ok; we all get lonely sometimes, and the theater is a big room full of warm bodies. Other media — for instance, Netflix; for instance, novels — comfort us in our loneliness, but by the same token, they enable it. Couldn’t theater do something different?

No doubt. But what if, instead, we thought about contemporary theater as a place where we could rehearse the perverse desire to burrow EVEN MORE DEEPLY into privacy? I don’t mean by repeating the tropes and mechanisms of the culture industry, which are working all the time to sustain our isolation, atomization, boutique identifications, etc. In fact, that’s probably what most theater (like most everything) does. But what if really unusual theater could intensify our solitude, defamiliarize it, and make it an object of pleasure in itself?

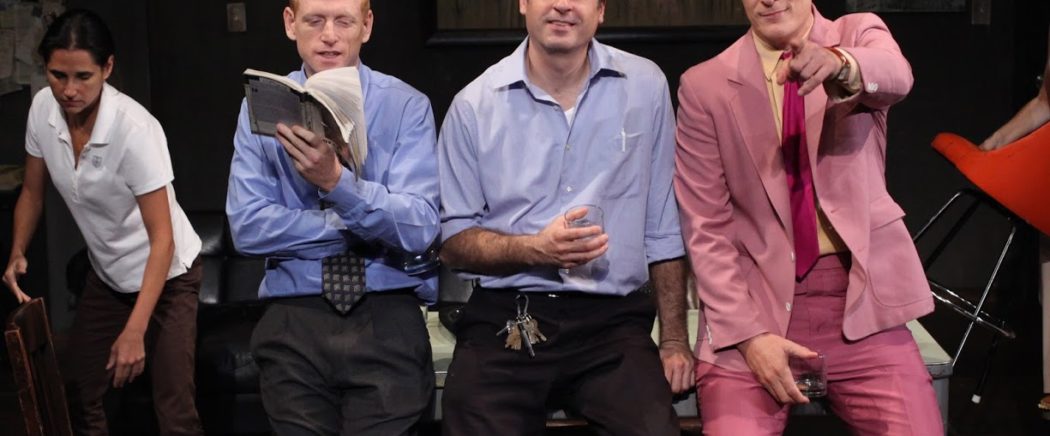

Gatz is a six-hour-plus-breaks performance by the New York company Elevator Repair Service. Surely one of the most written-about American theater pieces of the millennium (there is already at least one critical essay that analyzes tendencies in Gatz criticism), Gatz is a staging of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby (of which you may also have heard) in which every word of the novel is heard aloud. And in spite of — I mean because of — the mad virtuosity and hilarity of this company, how good they are at putting on a show, the weirdest thing happens over the course of this performance: you start to feel that the show IS the novel; I mean, that you and the book are alone together.

Isn’t this the opposite of what we need in our sad latter-day alienation? Shouldn’t we go to shows that make us feel EACH OTHER’s strength, the power of the collective that could be, if only we would just put our phones down? Actually, I suspect that Gatz’s dedication to privacy-in-public carries an ethical weight of its own. The way it gets us to feel the pleasure of disappearing into fantasy, the way it indulges our refusal to locate or discover ourselves in the social universe, might create a kind of cell for developing curmudgeonly powers of resistance to the info systems that have us at their beck and call. And then, you know, we might end up coming together for reasons better than loneliness.

Julia Jarcho, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of English at NYU. She is the author of “Writing and the Modern Stage: Theater Beyond Drama,” and an OBIE Award-winning playwright and director with the company, Minor Theater.