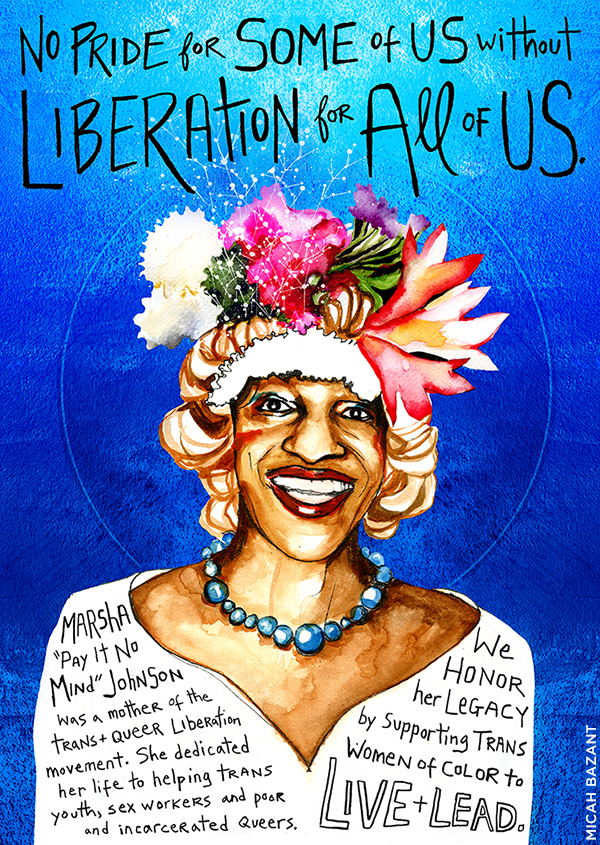

Micah Bazant, Portrait of Marsha P. Johnson

On June 28, 1969, a crowd of patrons at the Stonewall Inn rioted against a police raid, a flashpoint that is now commonly hailed as the first action towards a gay liberation movement. In the 50 years since “the shot glass heard round the world,” the story of Stonewall has grown to mythic proportions. We’ve come a long way since 1969 (here’s a timeline of queer history in the US to illustrate) but there’s still a long way to go, especially in relation to violence and discrimination against trans women of color – without whom, Stonewall would not have happened.

Learn more about Stonewall’s context and history in these readings, audio and videos, and join us for events that celebrate and uphold its legacy throughout 2019.

Read more about leaders like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera and their contributions to Stonewall and beyond.

Listen to an oral history of the night, including a first-hand account from Sylvia Rivera.

This concise write-up by June Thomas tells us just how far the Stonewall Inn itself has come, from the diviest of dive bars to a National Monument (thanks, Obama!).

In 1969, the Stonewall Inn at 51-53 Christopher Street was well-attended but not well-liked. Writer Vito Russo described it as “a regular hell hole. The pits. It was also one of the hottest dance bars in Greenwich Village. It was a bar for people who were too young, too poor or just too much to get in anywhere else. … A place everyone loved to hate. Seedy, loud, obvious and heaven.” People went there because it was relatively large, and because it was one of the few gay places in the Village that allowed dancing. But it had little else to recommend it.

As we celebrate 50 years of Stonewall, check out Chris E. Vargas’s Consciousness Razing: The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project (part of MOTHA: Museum of Transgender Hirstory and Art).

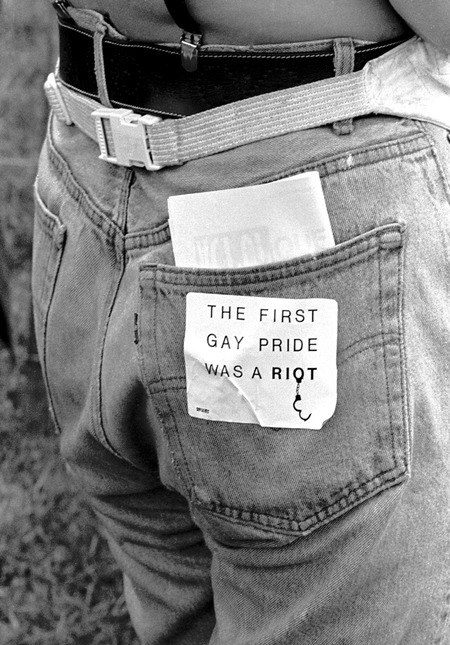

And don’t forget: the first gay pride was a riot! The activist organization Reclaim Pride is currently working to ensure the 2019 Pride March NYC “better represents the LGBTQIATS+ community.”

Reclaim Pride: learn more at reclaimpridenyc.org

Photographer unknown, circa 1991.

Stonewall’s legacy doesn’t begin and end with the legalization of same-sex marriage. In 2019, the precarity of queer people’s civil rights is front-page news every day – from discriminatory bathroom laws to trans military bans to queer immigrants dying in ICE custody.

Activist and advocacy groups like ACT UP, Rise & Resist, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, the Center, Hetrick-Martin Institute, SAGE, the Audre Lorde Project, and the NYC Anti-Violence Project are all NYC-based organizations that continue working locally to support and work towards queer and trans rights.

“It’s important to familiarize ourselves with who has fought with us, and who has fought against us — in other words, ‘know your scumbags.’”

“A surprisingly mainstream movement of feminists known as TERFs oppose transgender rights as a symptom of ‘female erasure.’”

“There was no need for the Supreme Court to reinstate a misguided ban on transgender service members.”

“The State Legislature voted overwhelmingly to bar mental health professionals from working to change a minor’s sexual orientation or gender identity.”

And if that’s not enough… A Queer History Reading List from University of California press.

Lesser known, but no less important: get into the histories of some of the uprisings that predate Stonewall. The times and places are different, but the common thread of trans women leading the community against police brutality remains the same. The Advocate puts together a list of 9 lesser-know actions that predate Stonewall. Fun fact, the Advocate was founded in the wake of the Black Cat Tavern protests.

Want to get more in-depth? Elizabeth Armstrong and Suzanna Crage consider why Stonewall takes precedence over these lesser-known histories: “Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth” (American Sociological Review v.71, 2006)

Stonewall was not the first of the five examined events to be viewed by activists as commemorable. It was, however, the first commemorable event to occur at a time and place where homosexuals had enough capacity to produce a commemorative vehicle—that is, where gay activists had adequate mnemonic capacity.

“Not too much is known about the uprising at Cooper’s Donuts, and as time passes, fewer of the storytellers of the time are around to share their experiences. But it is important to remember that the fight for LGBT rights was not limited to one city and one event.”

“Compton’s is mostly forgotten, which is doubly disappointing; it was one of the first known acts of resistance by queer people to police brutality, and the issue of improper policing remains one of the nation’s biggest flashpoints. Targeting, improper arrests, and police violence remain a huge issue for LGBT people of color.”

“The Black Cat… became the site of what was, at the time, the largest documented LGBTQ civil rights demonstration in the nation, leading many to recognize it as the birthplace of a worldwide movement… Hundreds gathered outside the bar in peaceful protest of police brutality and discriminatory laws and procedures.”

“Screaming Queens,” a documentary about the riots at Compton’s Cafeteria

You may have heard the fabulation that Stonewall was sparked by gay men’s grief at Judy Garland’s passing, in the hours after her funeral in June 1969 – this lore was recently shared again, in the “Best Judy” episode of the 2019 season of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars.

This makes for a great story, but – sorry, RuPaul! – it’s not the whole story. Calling Judy the catalyst of gay liberation belies the anger and frustration of decades of systemic abuse that sparked more than one uprising in the years preceding Stonewall, and the work of activists who advocated for gay liberation before the riots and who were quick to organize and make use of the momentum that followed, ultimately commemorating the first anniversary of the riot with the first gay pride parade.

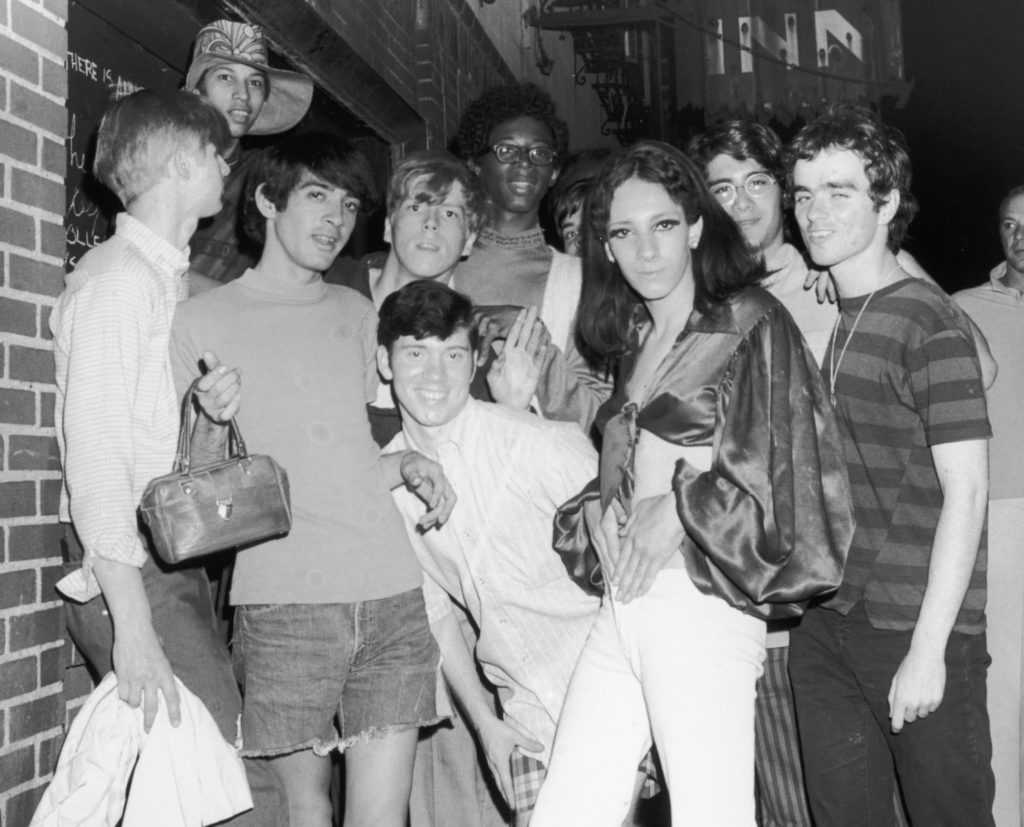

Photo credit: Fred W. McDarrah

Photo credit: Fred W. McDarrah

An interview with Stonewall participant Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt reflects on this theory and gives a first-hand account of the night – he’s in the striped shirt on the right, in the photo above. The Advocate points to David Carter’s book Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution, which finds no foundation for the Judy theory:

Only one historical document mentions Judy Garland and Stonewall together… a gossip column in the New York Mattachine Newsletter from August of 1969 which only brings up Garland’s death amid other gay news sundries.

In fact, one of the few pieces that links Garland’s death and the Stonewall Riots is a homophobic Village Voice column from July 10, 1969 called “Too Much, My Dear.” The heterosexual writer links the two to mock queer people.

“The combination of a full moon and Judy Garland’s funeral was too much for them,” Spencer writes in a paraphrased quote attributed to a friend. He calls Stonewall (in the next sentence) the Great Faggot Rebellion.

There’s similarly no mention of Garland in the New York Mattachine newsletter, which was reprinted in The Advocate in 1969.

But the conflation of these events is a sparkling example of camp as a queer survival strategy. The image of Stonewall as a hysterical outbreak of mourning queens may have started as a homophobic dismissal of the police brutality, violence and discrimination that so many queers faced daily – drag queens and trans women of color in particular – but it endures to paradoxically strengthen the mythology of Stonewall, building into something greater than a too-easily forgotten skirmish, or just another hot night in the West Village.

There’s something fabulous about the fact that Stonewall is shorthand for queer liberation when it also means “to be uncooperative, obstructive, or evasive.” There are a lot of bars in the West Village that could just as easily have been the flashpoint for the events of June 28, 1969 but none would have served as such an apt namesake. It’s a mark of the delicious, sharp-edged campiness of queer aesthetics that even our revolution will be punned. The double entendre insists: No complacency! No settling! No business as usual! We’re here, we’re queer, we’re mad as hell & we’re not going to take it anymore. Let us remember & carry this ethos with us into future fights.

The queer valence to the term should be added to dictionaries. Meanwhile, hear a bit more about stonewalling in Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Day podcast.